Raft

Raft is a consensus algorithm for managing replicated log. Raft separates the key elements of consensus, such as leader election, log replication, and safety, and it enforces a strong degree of coherency to reduce the number of states that must be considered. Raft is believed to be superior to Paxos and other consensus algorithms, both for educational purposes and as a foundation for implementation.

Consensus algorithm allows a collection of machines to work as a coherent group that can survive the failures of some of its members. Because of this, it plays a key role in building reliable large-scale software system.

Raft has a several novel features compared with existing consensus algorithm:

- Strong leader: Raft uses a stronger form of leadership than other consensus algorithm. For example, log entries only flow from the leader to other servers. This simplifies the management of the replicated log and makes Raft easier to understand.

- Leader election: Raft uses randomized timers to elect leaders. This adds only a small amount of mechanism to the the heartbeats already required for any consensus algorithm, while resolving conflicts simply and rapidly.

- Membership changes: Raft’s mechanism for changing the set of servers in the cluster uses a new joint consensus approach where the majorities of two different configurations overlap during transitions. This allows the cluster to continue operating normally during configuration changes.

Replicated state machines

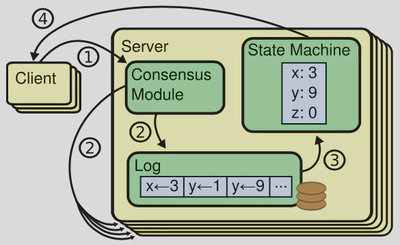

Consensus algorithms typically arise in the context of replicated state machines. In this approach, state machines on a collection of servers compute identical copies of the same state and can continue operating even if some of the servers are down. Replicated state machines are used to solve a variety of fault tolerance problems in distributed systems.

Replicated state machines are typically implemented using a replicated log. Each server stores a log containing a series of commands, which its state machine execute in order. Each log contains the same commands in the same order, so each state machine processes the same sequence of commands. Since the state machine are deterministic, each computes the same state and the same sequence of output.

Keeping the replicated log consistent is the job of the consensus algorithm The consensus module on a server receives command from clients and adds them to its log. It communicates with the consensus modules on other servers to ensure that every log eventually contains the same requests in the same order, even if some server fail. Once commands are properly replicated, each server’s state machine processes them in log order, and the outputs are returned to clients. As a result, the servers appear to form a single, highly reliable state machine.

The Raft consensus algorithm

Raft implements consensus by first electing a distinguished leader ,then giving the leader complete responsibility for managing the replicated log. The leader accepts log entries from clients, replicas them on other servers, and tells servers when it is safe to apply log entries to their state machines. Having a leader simplifies the management of replicated log. For example, the leader can decide where to place new entries in the log without consulting other servers, and data flows in a simple fashion from the leader to other servers. A leader can fail or become disconnected from other servers, in which case a new leader is elected.

Given the leader approach, Raft decomposes the consensus problem into three relatively independent sub-problems:

- Leader election: a new leader must be chosen when an existing leader fails.

- Log replication: the leader must accept log entries from clients and replicate them across the cluster, forcing the other logs to agree with its own.

- Safety: the key safety property for Raft is the State Machine Safety Property: if any server has applied a

particular log entry to its state machine, then no other server may apply a different command for the same log index.

- Election Safety: at most one leader can be elected in a given term.

- Leader Append-Only: a leader never overrides or deletes entries in its log: it only appends new entries.

- Log Matching: if two logs contains an entry with the same index and term, then the logs are identical in all entries up through the given index.

- Leader Completeness: if a log entry is committed in a given term, then that entry will be present in the logs of the leaders for all higher-numbered terms.

- State Machine Safety: if a server has applied a log entry at a given index to its state machine, no other server will ever apply a different log entry for the same index.

Raft basics

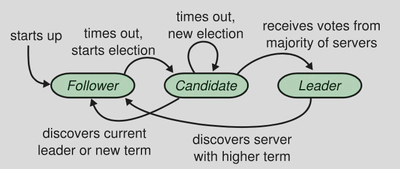

A Raft cluster contains several servers; five is a typical number, which allows the system to tolerate two failures. At any given time each server is in one of the three states: leader, follower, or candidate. In normal operation there is exactly one leader and all of the other servers are followers. Followers are passive: they issue no requests on their own but simply respond to requests from leaders and candidates. The leader handles all client requests(if a client contacts a follower, the follower redirects it to the leader). The third state, candidate, is used to elect a new leader.

Raft divides time into terms of arbitrary length. Terms are numbered with consecutive integers. Each term begins with an election, in which one or more candidates attempt to become leaders. If a candidate wins the election, then it serves as leader for the rest of the term. In some situations, an election will result in a split vote. IN this case th term will end with no leader; a new term(with a new election) will begin shortly. Raft ensures that there is at most one leader in a given term.

Different servers may observe the transitions between terms at different times,a nd in some situations a server may not observe an election or even entire terms. Terms act as logical clock in Raft and they allow server to detect obsolete information such as stale leaders. Each server stores a current term number, which increase monotonically over time. Current terms are exchanged whenever server communicate; if one server’s current term is smaller than the other’s, then it updates it current term to the larger value. If a candidate or leader discovers that its term is out of date, it immediately reverts to follower state. If a server receives a request with a stale term number, it rejects the request.

Raft servers communicate using remote procedure calls:

- RequestVote RPCs are initiated by candidates during election

- AppendEntries RPCs are initiated by leaders to replicate log entries and to provider a form of heartbeat

- InstallSnapshot RPCs are initiated by leader to send snapshots to followers that are too far behind

Servers retry RPCs if they do not receive a response in a timely manner, and they issue RPCs in parallel for best performance.

Leader election

Raft uses a heartbeat mechanism to trigger leader election. When servers start up, they begin as followers. A server remains in follower state as long as it receives valid RPCs from a leader or candidate. Leaders send periodic heartbeats(AppendEntries RPCs that carry no log entries) to all followers in order to maintain their authority. If a follower receives no communication over a period of time called the election timeout, then it assumes there is no viable leader and begins an election to choose a new leader.

To begin an election, a follower increments its current term and transitions to candidate state. It then votes for itself and issues RequestVote RPCs in parallel to each of the other servers in the cluster. A candidate continues in this state until one of three things happens:

- it wins the election

- another server establishes itself as leader, or

- a period of time goes by with no winner

Raft uses randomized election timeouts to ensure that split votes are rare and that they are resolved quickly. Each candidate restarts its randomized election timeout at the start of an election, and it waits for that timeout to elapse before starting the next election.

Log replication

Once a leader has been elected, it begins servicing client requests. Each client request contains a command to be executed by the replicated state machines. The leader appends the command to its log as a new entry, then issues AppendEntries RPCs in parallel to each of the other servers to replicate the entry. When the entry has been safely replicated, the leader applies the entry to its state machine and returns the result of that execution to the client. If followers crash or run slowly, or if network packets are lost, the leader retries AppendEntries RPCs indefinitely (even after it has responded to the client) until all followers eventually store all log entries.

The leader decides when it is safe to apply a log entry to the state machines; such an entry is called committed. Raft guarantees that committed entries are durable and will eventually be executed by all of the available state machines. A log entry is committed once the leader that created the entry has replicated it on a majority of the servers. This also commits all preceding entries in the leader’s log, including entries created by previous leaders.

Raft maintains the following properties, which together constitute the Log Matching Property:

- If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then they store the same command.

- If two entries in different logs have the same index and term, then the logs are identical in all preceding entries.

The first property follows from the fact that a leader creates at most one entry with a given log index in a given term, and log entries never change their position in the log. The second property is guaranteed by a simple consistency check performed by AppendEntries. When sending an AppendEntries RPC, the leader includes the index and term of the entry in its log that immediately precedes the new entries. If the follower does not find an entry in its log with the same index and term, then it refuses the new entries. The consistency check acts as an induction step: the initial empty state of the logs satisfies the Log Matching Property, and the consistency check preserves the Log Matching Property whenever logs are extended. As a result, whenever AppendEntries returns successfully, the leader knows that the follower’s log is identical to its own log up through the new entries.

In Raft, the leader handles inconsistencies by forcing the followers’ logs to duplicate its own. This means that conflicting entries in follower logs will be overwritten with entries from the leader’s log.

To bring a follower’s log into consistency with its own, the leader must find the latest log entry where the two logs agree, delete any entries in the follower’s log after that point, and send the follower all of the leader’s entries after that point. All of these actions happen in response to the consistency check performed by AppendEntries RPCs. When a leader first comes to power, it initializes all nextIndex values to the index just after the last one in its log. If a follower’s log is inconsistent with the leader’s, the AppendEntries consistency check will fail in the next AppendEntries RPC. After a rejection, the leader decrements nextIndex and retries the AppendEntries RPC. Eventually nextIndex will reach a point where the leader and follower logs match. When this happens, AppendEntries will succeed, which removes any conflicting entries in the follower’s log and appends entries from the leader’s log (if any). Once AppendEntries succeeds, the follower’s log is consistent with the leader’s, and it will remain that way for the rest of the term.

Safety

The mechanisms described so far are not quite sufficient to ensure that each state machine executes exactly the same commands in the same order. To complete the Raft algorithm, we need to add a restriction on which servers may be elected leader.

Raft uses the voting process to prevent a candidate from winning an election unless its log contains all committed entries. A candidate must contact a majority of the cluster in order to be elected, which means that every committed entry must be present in at least one of those servers. If the candidate’s log is at least as up-to-date as any other log in that majority (where “up-to-date” is defined precisely below), then it will hold all the committed entries. The RequestVote RPC implements this restriction: the RPC includes information about the candidate’s log, and the voter denies its vote if its own log is more up-to-date than that of the candidate. Raft determines which of two logs is more up-to-date by comparing the index and term of the last entries in the logs.

Timing and availability

Raft is that safety must not depend on timing: the system must not produce incorrect results just because some event happens more quickly or slowly than expected. However, availability (the ability of the system to respond to clients in a timely manner) must inevitably depend on timing.

Leader election is the aspect of Raft where timing is most critical. Raft will be able to elect and maintain a steady leader as long as the system satisfies the following timing requirement:

1broadcastTime ≪ electionTimeout ≪ MTBF

In this inequality broadcastTime is the average time it takes a server to send RPCs in parallel to every server in the cluster and receive their responses; electionTimeout is the election timeout; and MTBF is the average time between failures for a single server.

Cluster membership changes

Up until now we have assumed that the cluster configuration (the set of servers participating in the consensus algorithm) is fixed. In practice, it will occasionally be necessary to change the configuration, for example to replace servers when they fail or to change the degree of replication.

For the configuration change mechanism to be safe, there must be no point during the transition where it is possible for two leaders to be elected for the same term.

In order to ensure safety, configuration changes must use a two-phase approach. In Raft the cluster first switches to a transitional configuration we call joint consensus; once the joint consensus has been committed, the system then transitions to the new configuration. The joint consensus combines both the old and new configurations:

- Log entries are replicated to all servers in both configurations.

- Any server from either configuration may serve as leader.

- Agreement(for elections and entry commitment) requires separate majorities from both the old and new configurations.

Log compaction

As the log grows longer, it occupies more space and takes more time to replay. This will eventually cause availability problems without some mechanism to discard obsolete information that has accumulated in the log.

Snapshotting is the simplest approach to compaction. In snapshotting, the entire current system state is written to a snapshot on stable storage, then the entire log up to that point is discarded.

Each server takes snapshots independently, covering just the committed entries in its log. Most of the work consists of the state machine writing its current state to the snapshot. Raft also includes a small amount of metadata in the snapshot: the last included index is the index of the last entry in the log that the snapshot replaces (the last entry the state machine had applied), and the last included term is the term of this entry.

Although servers normally take snapshots independently, the leader must occasionally send snapshots to followers that lag behind. The leader uses a new RPC called InstallSnapshot to send snapshots to followers that are too far behind. When a follower receives a snapshot with this RPC, it must decide what to do with its existing log entries. Usually the snapshot will contain new information not already in the recipient’s log. In this case, the follower discards its entire log; it is all superseded by the snapshot and may possibly have uncommitted entries that conflict with the snapshot. If instead the follower receives a snapshot that describes a prefix of its log (due to retransmission or by mistake), then log entries covered by the snapshot are deleted but entries following the snapshot are still valid and must be retained.

Client interaction

Clients of Raft send all of their requests to the leader. When a client first starts up, it connects to a randomly-chosen server. If the client’s first choice is not the leader, that server will reject the client’s request and supply information about the most recent leader it has heard from (AppendEntries requests include the network address of the leader). If the leader crashes, client requests will time out; clients then try again with randomly-chosen servers.

Our goal for Raft is to implement linearizable semantics (each operation appears to execute instantaneously, exactly once, at some point between its invocation and its response) The solution is for clients to assign unique serial numbers to every command. Then, the state machine tracks the latest serial number processed for each client, along with the associated response. If it receives a command whose serial number has already been executed, it responds immediately without re-executing the request.

Read-only operations can be handled without writing anything into the log. However, with no additional measures, this would run the risk of returning stale data, since the leader responding to the request might have been superseded by a newer leader of which it is unaware. Linearizable reads must not return stale data, and Raft needs two extra precautions to guarantee this without using the log. First, a leader must have the latest information on which entries are committed. The Leader Completeness Property guarantees that a leader has all committed entries, but at the start of its term, it may not know which those are. To find out, it needs to commit an entry from its term. Raft handles this by having each leader commit a blank no-op entry into the log at the start of its term. Second, a leader must check whether it has been deposed before processing a read-only request (its information may be stale if a more recent leader has been elected). Raft handles this by having the leader exchange heartbeat messages with a majority of the cluster before responding to read-only requests.